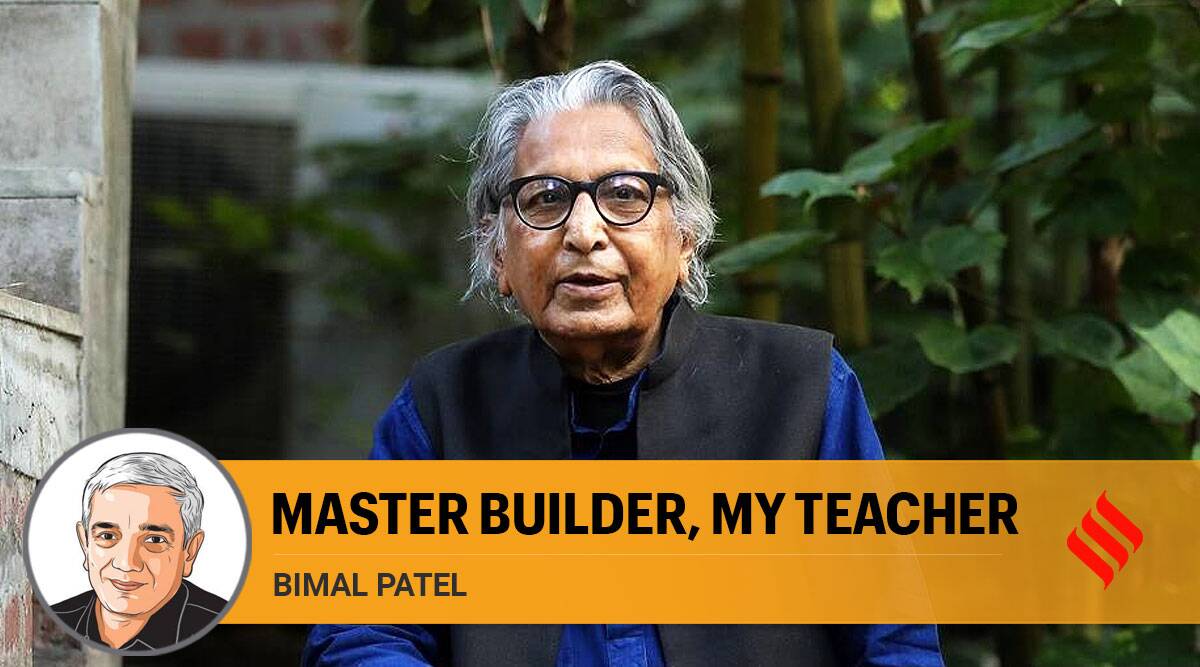

Balkrishna Doshi was a great Indian architect whose passing marks the end of an era. He contributed immensely to the enrichment of Indian architecture, not only through his many fine works, but also by founding a school of architecture in Ahmedabad that continues to be a beacon of innovation and excellence. Doshi was also a great champion of the architectural profession who through his talks, writings, research projects and advocacy kept the profession’s flag flying high.

Doshi was born in 1927 and grew up in Pune. He studied architecture at the J J School of Art, Mumbai. Starting in 1951 he worked in Paris with Le Corbusier and then returned to India to represent him in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad. He set up his practice in 1958 in Ahmedabad and lived there throughout his life. He was conferred with many awards including the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, the Pritzker Prize and the Padma Bhushan.

Doshi’s engagement in architectural practice, which continued well into his nineties, was prolific. In the modern architecture that emerged in India after Independence, he epitomised the more artistic or romantic approach. His works ranged from small houses, institutional buildings and offices to large housing projects, campuses, and townships. Many of his projects, such as the School of Architecture at CEPT, the Institute of Indology, Hussain Doshi Gufa, his own office called Sangath, his own home and Tagore Hall have become iconic. They are a part of the subconscious of Indian architects.

Amongst his many works, the School of Architecture at Ahmedabad is an absolute gem and my favourite. No linear description of the building is possible. One can only list impressions: Proud and robust exposed brick walls forming 10-metre-wide bays; exposed concrete floors stepping front and back, forming great double height volumes; north lights taken from an industrial idiom; an iconic ramp that leads you up to two beautiful splayed stairs that channel you into the depth of the building; a half-basement that opens out onto a lawn on one side and a brick-paved plaza on the other; a magnificent alley formed by two great brick walls that leads you up to a great portal; an elevation formed by arrays of handsome wood-panelled doors that open out onto balconies; simple kota stone floors; vistas that unfold as one moves through the spaces. Like a great work of art, its enchanting beauty can only be experienced. It is a jewel on CEPT University’s campus that has recently been restored and is well worth a visit to Ahmedabad for.

In the early sixties, Doshi convinced Kasturbhai Lalbhai, Ahmedabad’s legendary industrialist and philanthropist, to fund the establishment of a school of architecture. Under Doshi’s leadership and with the support of co-founders Bernard Kohn, Rasu Vakil and many other practicing architects that he drew into the school, it soon became a vibrant centre of modern architectural education. Its pedagogy was infused with Doshi’s liberal and cosmopolitan values. It also benefited much from Doshi’s international vision and desire to speak to the world. It ensured that the school was continuously visited by many renowned architects. On account of this, even when India was relatively closed to the world, students remained in touch with what was going on in the world of architecture outside India. In the early seventies, Doshi collaborated with Christopher Benninger to establish the School of Planning. This school also soon became an important centre for planning education. Fifty years later, both schools are now part of CEPT University and continue to be nourished by the values that Doshi infused them with.

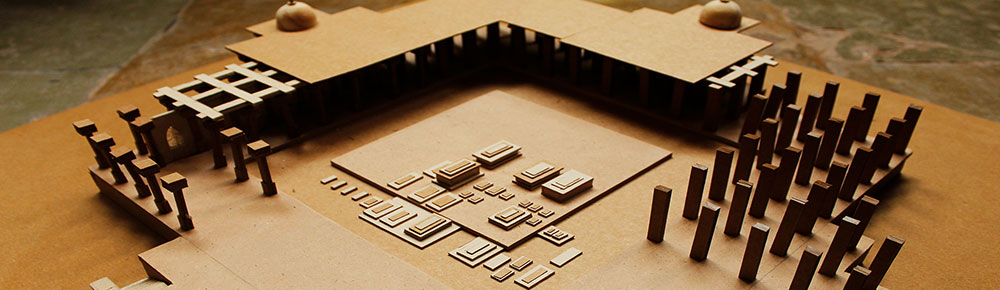

I studied at the school that Doshi founded. Though he was no longer actively teaching, his inspiring presence in the architecture world of Ahmedabad had a great influence on my formation. I remember visiting Doshi’s office many times when I was a student. It was like a great laboratory of architecture where many different problems, large and small, were being tackled and many different ideas were being explored through amazing drawings and models. The office was incredibly vibrant and awe-inspiring and my visits left a lasting impression on me. Even now those impressions continue to inspire me.

He was, for me, “Doshi kaka” — my father’s friend and fellow practicing architect. The two got to know each in the early sixties soon after my father arrived in Ahmedabad. Doshi had already set up his practice and founded a new school of architecture. He invited my father to teach and our families got to know one another closely. Temperamentally and in their view of architecture, my father and Doshi were quite different. My father, more rational and systematic in his stance, contrasted with Doshi’s more artistic and individualistic approach to architecture. But their differing approaches did not stop them from respecting each other’s commitment to excellence in architecture. They admired one another and enjoyed a warm friendship. Doshi’s passing is a deep personal loss and I grieve with his family.